During the Antebellum Period, the port of Washington, N.C. was a major shipbuilding center for North Carolina. But did you know that one of Washington’s most successful shipbuilders was a “freedman,” a former slave who had been granted his liberty by his former owner and rose to be one of Washington’s most successful businessmen? His name was Hull Anderson. Anderson’s story is one of a thriving entrepreneur but ends in the eventual abandonment of his home and business in Washington, N.C. for life in a strange country. But why would he desert Washington and take his chances in a foreign land?

During the Antebellum Period, the port of Washington, N.C. was a major shipbuilding center for North Carolina. But did you know that one of Washington’s most successful shipbuilders was a “freedman,” a former slave who had been granted his liberty by his former owner and rose to be one of Washington’s most successful businessmen? His name was Hull Anderson. Anderson’s story is one of a thriving entrepreneur but ends in the eventual abandonment of his home and business in Washington, N.C. for life in a strange country. But why would he desert Washington and take his chances in a foreign land?

Immediately following the American Revolution, a sentiment existed among many citizens that the institution of slavery was morally wrong. During the first quarter of the 19th Century, progress was made toward granting freedom and equality to slaves. In North Carolina, as in other Southern states, the population of free African-Americans increased as numerous slaves were able to acquire their freedom through manumission, the formal act of freeing a slave by an owner, or through the outright purchase of their own freedom. Washington experienced a similar trend. Census records tell us the population in Washington of “free people of color” increased from just 8 in 1800 to over 200 by 1860. The white population grew from 288 to 1503 during the same period.

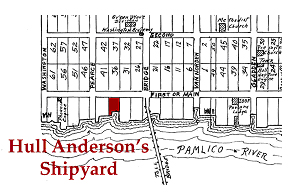

Wingate Reed informs us in his book Beaufort County, Two Centuries of History that Hull Anderson was granted his freedom by 1826. Anderson took his name from his former owners John and Sally Anderson of Beaufort County. One wonders if his given name “Hull” might be a sign of his shipbuilding talent acquired as a slave. After his manumission, Anderson apparently worked in a shipyard in Washington for a period of time acquiring significant assets. By 1826, Anderson built a house on a lot in Respass Town. That same year, he bought a slave named “Esther,” possibly his daughter, from his former master Sally Anderson. In 1827 Anderson purchased another enslaved woman, “Chaney” or “Cherry” who we know was his wife. In 1830, Anderson established his own shipyard on the waterfront on a lot purchased from Bryan Grimes, later famous as a Civil War general and plantation owner. In the 1840 U.S. Census of Washington, Hull Anderson is listed as living with 3 other 'free persons of color' and 1 female slave. Hull Anderson’s shipbuilding business thrived on this lot, 519 West Main Street, until about 1841.

Wingate Reed informs us in his book Beaufort County, Two Centuries of History that Hull Anderson was granted his freedom by 1826. Anderson took his name from his former owners John and Sally Anderson of Beaufort County. One wonders if his given name “Hull” might be a sign of his shipbuilding talent acquired as a slave. After his manumission, Anderson apparently worked in a shipyard in Washington for a period of time acquiring significant assets. By 1826, Anderson built a house on a lot in Respass Town. That same year, he bought a slave named “Esther,” possibly his daughter, from his former master Sally Anderson. In 1827 Anderson purchased another enslaved woman, “Chaney” or “Cherry” who we know was his wife. In 1830, Anderson established his own shipyard on the waterfront on a lot purchased from Bryan Grimes, later famous as a Civil War general and plantation owner. In the 1840 U.S. Census of Washington, Hull Anderson is listed as living with 3 other 'free persons of color' and 1 female slave. Hull Anderson’s shipbuilding business thrived on this lot, 519 West Main Street, until about 1841.

Changing circumstances in the South did not forebode well for Anderson. The increased profitability of growing cotton made possible by the invention of the cotton gin and the need for cheap labor caused the enslaved population of North Carolina to swell from 102,726 in 1790 to 331,059 in 1860. Tensions rising from slave rebellions in nearby states and the rise of the abolitionist movement made the white slave owners suspicious of free African-Americans. Concerns grew that they would encourage unrest amongst the enslaved population. From 1826 through the 1850s, North Carolina passed a series of restrictive laws referred to as the "Free Negro Code". Measures such as harshly limiting the travel of free African-Americans and requiring them to obtain a permit to carry a gun were passed. Finally, in 1835, the suffrage of free African-Americans was abolished.

Hull Anderson must have resolved that continuing to live in North Carolina as a freedman did not hold much promise. In 1841 he sold most of his property in Washington and emigrated by way of Norfolk to Liberia, a colony on the tropical west coast of Africa. Liberia was established in 1820 by the American Colonization Society, a group who believed African-Americans faced better chances for full lives in Africa than they did in the United States. The voyage began on November 1 and ended some 40 days later on December 12, 1841.

An 1843 census of the colony shows Hull Anderson, age 50, living in the town of Monrovia along with his wife Cherry and son Henry. Anderson had given up the profession of shipbuilder and was listed as a farmer owning 100 acres of land, 2 buildings, and 100 coffee trees. Hull Anderson died on July 19, 1852, followed ten years later by his wife Cherry.

Hull Anderson’s story is a sign of how tumultuous life and politics must have been in North Carolina for "free persons of color" prior to the Civil War. So ends the story of a once promising career of a successful shipbuilder and landowner in the town of Washington, N.C.